NATURE Notes

Every month there will be a new note about what to look for in the natural world during that month.

June - underwater architects: Caddisfly Larvae

Photo By: Bob Henricks

Photo By: Bob Henricks

The Jay C. Hormel Nature Center is home to so many critters, but not many know about the plethora of them that live under the surface of our waters. Both our pond and Dobbins Creek are amazing habitats for all sorts of aquatic macroinvertebrates which is a fancy phrase for all sorts of water creepy crawlies that don’t have a backbone, like bugs, or crayfish. Those aquatic insects are usually in their mid-life stage underwater before they become their better-known adult stages in the air and on land, like dragonflies, damselflies, mayflies, etc.

One of the coolest macroinvertebrates in the creek scene are little grub looking insects called caddisfly larvae. Their adult form is similar looking to a moth that lives for about 4 months. Most of their life is spent in their aquatic larval stage, which could last a couple of years hanging out in streams and rivers. While the appearance of these glorified worm looking inverts is nothing to write home about, they are incredibly talented underwater architects.

Caddisflies larvae produce sticky silk because of modified salivary glands. Can you imagine being able to spit out double sided tape on command that works in water? What a party trick. These larvae take this sticky silk and construct a huge variety of different structures. Some of them will create intricate tubes made from individual grains of sand, pebbles, or plant material. While others can make more of a snail shell shape, or even just weave a net out of silk. After the construction, the caddisflies that build these tubes, called casings, crawl inside, like a hermit crab does. They will attach themselves with their newly self-constructed home to a rock on the bottom of the stream bed to lie in wait for food to come to them.

An up-close look at these little architects proudly hunkered down in their casing will showcase three pairs of legs and heads hanging out the front to catch a meal from the water current on the way by. The front of their heads house large pincers that help chomp through dead organic material including algae and leaves, called detritus.

It is easy to spot caddisflies as most are attached to rocks on creek bed floors. You can find small streaks of webbing silk, suspicious rocks clumped together, or, if you are lucky, find intact casings if you turn over rocks in a cold, fast moving creek. In recent years more and more caddisflies and their casings have been found in Dobbins Creek at the nature center which is a great indication of water quality. Caddisflies, along with some other macroinvertebrates, have a low tolerance to pollutants in the water where they reside. Meaning the more that we find, the cleaner our water quality is.

Caddisflies, stoneflies, mayflies, and other aquatic macroinvertebrates are a primary food source for larger aquatic animals that live in streams, including trout. An increase in these pollutant intolerant aquatic macroinvertebrates shows us that there has been an improvement to the water quality over the past few decades. Next time you are enjoying time at a babbling brook or taking a stroll next to Dobbins Creek at the nature center, know that there’s a lot happening beneath the water’s surface.

Author: Outreach Naturalist – Kelly Bahl

One of the coolest macroinvertebrates in the creek scene are little grub looking insects called caddisfly larvae. Their adult form is similar looking to a moth that lives for about 4 months. Most of their life is spent in their aquatic larval stage, which could last a couple of years hanging out in streams and rivers. While the appearance of these glorified worm looking inverts is nothing to write home about, they are incredibly talented underwater architects.

Caddisflies larvae produce sticky silk because of modified salivary glands. Can you imagine being able to spit out double sided tape on command that works in water? What a party trick. These larvae take this sticky silk and construct a huge variety of different structures. Some of them will create intricate tubes made from individual grains of sand, pebbles, or plant material. While others can make more of a snail shell shape, or even just weave a net out of silk. After the construction, the caddisflies that build these tubes, called casings, crawl inside, like a hermit crab does. They will attach themselves with their newly self-constructed home to a rock on the bottom of the stream bed to lie in wait for food to come to them.

An up-close look at these little architects proudly hunkered down in their casing will showcase three pairs of legs and heads hanging out the front to catch a meal from the water current on the way by. The front of their heads house large pincers that help chomp through dead organic material including algae and leaves, called detritus.

It is easy to spot caddisflies as most are attached to rocks on creek bed floors. You can find small streaks of webbing silk, suspicious rocks clumped together, or, if you are lucky, find intact casings if you turn over rocks in a cold, fast moving creek. In recent years more and more caddisflies and their casings have been found in Dobbins Creek at the nature center which is a great indication of water quality. Caddisflies, along with some other macroinvertebrates, have a low tolerance to pollutants in the water where they reside. Meaning the more that we find, the cleaner our water quality is.

Caddisflies, stoneflies, mayflies, and other aquatic macroinvertebrates are a primary food source for larger aquatic animals that live in streams, including trout. An increase in these pollutant intolerant aquatic macroinvertebrates shows us that there has been an improvement to the water quality over the past few decades. Next time you are enjoying time at a babbling brook or taking a stroll next to Dobbins Creek at the nature center, know that there’s a lot happening beneath the water’s surface.

Author: Outreach Naturalist – Kelly Bahl

Previous nature notes

2024 NATURE NOTES

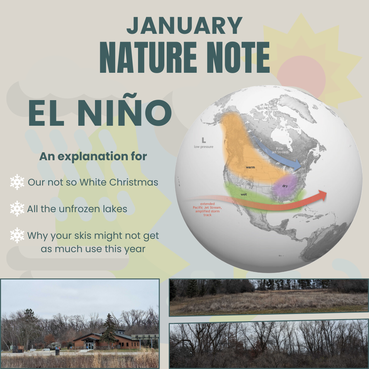

January - el niño

Many Minnesotans have been saying that winter is looking pretty different this year. For many, our lack of a white Christmas prompted folks to start wondering just what was happening with our weather. After all we already had a dry, hot summer, so why are we also having a dry winter? We can credit this to a climate pattern known as El Niño which causes changes in currents and the jet stream.

Depending on where you are on Earth, your climate and weather are subject to different air and ocean currents that circulate the globe. In a typical year, the trade winds, which are located along the equator, flow over the ocean and move warmer water west, away from South America and towards Asia. This shift of warmer water causes an event called upwelling, where cold water rises upward to replace the, now absent, warmer water. Upwelling events in the ocean help cycle nutrients from the bottom of the ocean closer to the surface. These areas of upwelling have greater biological diversity and higher populations of fish, zooplankton, and phytoplankton.

El Niño years are not typical years. El Niño refers to a global pattern of weather that weakens the trade winds and breaks the normal cycles of upwelling. When trade winds weaken, the warmer water that was normally pushed west, now moves east towards the west coast of the United States. This halts the usual cycles of upwelling that would normally occur along the coast and shifts another air current, the Pacific Jet Stream, south. Jet streams are very strong bands of wind located in the upper atmosphere that blow at very high speeds. The location of the jet stream influences areas of high and low pressure on the ground which can create different weather patterns. For example, Polar Vortexes are formed when the Polar Jet Stream shifts south.

During an El Niño period, because the Pacific Jet Stream shifts, places in the American Southwest which are typically very dry and desert-like, become floodplains. Areas in the Northern United States which typically receive more rain and relatively mild summers will experience dry, hot summers like we did in Minnesota this year. This dry weather pattern continues into the winter months with the northern United States experiencing significantly less snowfall.

El Niño doesn’t last forever though. On average, El Niño episodes last for about 9-12 months, but this climate pattern can sometimes push on for longer. We can expect an El Niño episode to occur about every 2-7 years. Our last El Niño episode lasted from late 2018 to mid-2019.

Author: Ryen Nielsen – Teacher/Naturalist Intern

Depending on where you are on Earth, your climate and weather are subject to different air and ocean currents that circulate the globe. In a typical year, the trade winds, which are located along the equator, flow over the ocean and move warmer water west, away from South America and towards Asia. This shift of warmer water causes an event called upwelling, where cold water rises upward to replace the, now absent, warmer water. Upwelling events in the ocean help cycle nutrients from the bottom of the ocean closer to the surface. These areas of upwelling have greater biological diversity and higher populations of fish, zooplankton, and phytoplankton.

El Niño years are not typical years. El Niño refers to a global pattern of weather that weakens the trade winds and breaks the normal cycles of upwelling. When trade winds weaken, the warmer water that was normally pushed west, now moves east towards the west coast of the United States. This halts the usual cycles of upwelling that would normally occur along the coast and shifts another air current, the Pacific Jet Stream, south. Jet streams are very strong bands of wind located in the upper atmosphere that blow at very high speeds. The location of the jet stream influences areas of high and low pressure on the ground which can create different weather patterns. For example, Polar Vortexes are formed when the Polar Jet Stream shifts south.

During an El Niño period, because the Pacific Jet Stream shifts, places in the American Southwest which are typically very dry and desert-like, become floodplains. Areas in the Northern United States which typically receive more rain and relatively mild summers will experience dry, hot summers like we did in Minnesota this year. This dry weather pattern continues into the winter months with the northern United States experiencing significantly less snowfall.

El Niño doesn’t last forever though. On average, El Niño episodes last for about 9-12 months, but this climate pattern can sometimes push on for longer. We can expect an El Niño episode to occur about every 2-7 years. Our last El Niño episode lasted from late 2018 to mid-2019.

Author: Ryen Nielsen – Teacher/Naturalist Intern

February - I Spy signs of spring

The dark, cold nights are coming to an end as February begins. As a naturalist, I am always outside and looking for the natural changes in nature that signify the changing seasons. Not only are we getting more sunlight every day, but because of this, we are starting to slowly see the signs of spring! One of my favorite quotes is from Naturalist John Trott from Virgina: “So, the year is turning and moving inexorably toward spring which, once started, moves like a snowball rolling downhill. It gathers momentum and mass until early May when each day brings so much newness that I am impatient and exasperated with my inability to see and hear it all. For now, I’ll concentrate on the slow momentum of February”.

Now is the perfect time to start a nature journal. There are no rules for a nature journal! Write down what you see that is new/changing, what you love about nature, write it like a story or write down bullet points. So as you start coming out of your hibernation with the increase of sunlight, here are the things that will be joining you.

Becoming more aware of the little things going on in nature that are signs of spring not only gets you out of your winter slump but also keeps you motivated to continue exploring nature. Keeping a nature journal is a great activity to do with kids. It works on their observation skills, writing skills, and possibly even art if they choose to draw in their journals. Get out there and start enjoying the weather!

Author: Sydney Weisinger – Teacher/Naturalist

Now is the perfect time to start a nature journal. There are no rules for a nature journal! Write down what you see that is new/changing, what you love about nature, write it like a story or write down bullet points. So as you start coming out of your hibernation with the increase of sunlight, here are the things that will be joining you.

- Chickadees are singing “fee-bee” while eating their weight in food each day.

- Early February you can hear woodpeckers drumming on trees and calling. Their call sounds like a crackle.

- Coyotes become more active during mating season.

- Raccoons come out of their winter dens early on warm February days.

- American crows start to migrate north. They winter and travel in flocks. Once they reach their summer homes, they become solitary nesters with their mate.

- Great horned owls are Minnesota’s earliest nesting bird. They will be sitting on eggs by the second week of February.

- Barred owls are hooting at each other in the forest, setting their territories.

- Moss and lichens green up with the humid air and higher sun.

- Tree squirrels are very vocal are chasing perspective mates through the trees.

- Flocks of horned larks are seen along the roadways as one of the first spring migrants.

- By the end of February, red-tailed hawks start returning to their nesting sites.

- Keep an eye out for the first chipmunk emerging by the end of February.

- If you hear a loud double squawk, it is the sound of a male ring-necked pheasant courting.

- Look out for yellow coming back to male American goldfinches’ feathers.

- White-tailed deer start shedding their winter fur towards the end of February.

Becoming more aware of the little things going on in nature that are signs of spring not only gets you out of your winter slump but also keeps you motivated to continue exploring nature. Keeping a nature journal is a great activity to do with kids. It works on their observation skills, writing skills, and possibly even art if they choose to draw in their journals. Get out there and start enjoying the weather!

Author: Sydney Weisinger – Teacher/Naturalist

March - The Mycelium Matrix

We’re all familiar with the many colorful, beautiful, and downright strange mushrooms that pop up during the summer and fall. Mushrooms can take on many different shapes and sizes, but the mushrooms that we see and love are only one small portion of the fungi we don’t see. The main body of a fungus is not the mushrooms we see above ground but rather millions of tiny white strands stretching out underground. These strands are known as mycelium. Mycelium is the main body of a fungus and they look and act like the roots and branches of trees. If you’ve ever seen mold on cheese or bread, then you know what mycelium looks like. Mold is just thousands of strands mycelium stacked on top of each other.

Mycelium grows one cell at a time and is very compact, so tens of miles of mycelium can only take up one pound soil. Even though mycelium is compact, that doesn’t mean it can’t stretch far. Fungi growing close together are just as likely to be a part of the same mycelium network, or body, as mushrooms growing miles apart. In fact, the world’s largest organism is a honey fungus growing in Oregon that stretches over 3.6 square miles!

Mycelium is responsible for taking in nutrients, communicating with other fungi, and reproducing. The mushrooms that we see above ground are one way that fungi reproduce. The mushrooms send out spores that are usually carried by the wind, and these spores land in a new location and establish themselves by sending out mycelium strands into the soil. However, mushrooms can only pop up when environmental conditions are just right, so fungi can also reproduce by splitting their mycelium. If a section of mycelium dies off somehow, causing two sections of the mycelium to be separated, the sections will split apart and begin to live as two different fungi.

Most fungi are detritivores, meaning they eat dead things, so the mycelium will feed the fungus by releasing enzymes that break down leaves, bark, and dead critters. Some fungi are not detritivores and instead feed by living in symbiosis with certain trees or plants, these fungi are known as mycorrhizal fungi. The mycelium of these fungi act as extensions of the roots of the plant and will bring in any water or nutrients it’s able to find in the soil. The fungus takes enough nutrients and water to sustain itself and gives the rest to its plant partner.

Without the mycelium networks of fungi, we’d be buried beneath thousands of dead trees, critters, and the soil in our gardens wouldn’t be able to grow things. Mycelium networks are the work horses of the decomposer food web and a leg up to many plants that have a mycorrhizal partner. Even though we usually only think of mushrooms as something that pops up after rainy weather, they’re around all year, working hard, just beneath our feet.

Author: Ryen Nielsen – Teacher/Naturalist Intern

Mycelium grows one cell at a time and is very compact, so tens of miles of mycelium can only take up one pound soil. Even though mycelium is compact, that doesn’t mean it can’t stretch far. Fungi growing close together are just as likely to be a part of the same mycelium network, or body, as mushrooms growing miles apart. In fact, the world’s largest organism is a honey fungus growing in Oregon that stretches over 3.6 square miles!

Mycelium is responsible for taking in nutrients, communicating with other fungi, and reproducing. The mushrooms that we see above ground are one way that fungi reproduce. The mushrooms send out spores that are usually carried by the wind, and these spores land in a new location and establish themselves by sending out mycelium strands into the soil. However, mushrooms can only pop up when environmental conditions are just right, so fungi can also reproduce by splitting their mycelium. If a section of mycelium dies off somehow, causing two sections of the mycelium to be separated, the sections will split apart and begin to live as two different fungi.

Most fungi are detritivores, meaning they eat dead things, so the mycelium will feed the fungus by releasing enzymes that break down leaves, bark, and dead critters. Some fungi are not detritivores and instead feed by living in symbiosis with certain trees or plants, these fungi are known as mycorrhizal fungi. The mycelium of these fungi act as extensions of the roots of the plant and will bring in any water or nutrients it’s able to find in the soil. The fungus takes enough nutrients and water to sustain itself and gives the rest to its plant partner.

Without the mycelium networks of fungi, we’d be buried beneath thousands of dead trees, critters, and the soil in our gardens wouldn’t be able to grow things. Mycelium networks are the work horses of the decomposer food web and a leg up to many plants that have a mycorrhizal partner. Even though we usually only think of mushrooms as something that pops up after rainy weather, they’re around all year, working hard, just beneath our feet.

Author: Ryen Nielsen – Teacher/Naturalist Intern

April - Canada Geese Family Rearing

A month ago, V-shaped flocks peppered our skies. With their populations increasing fast in the Midwest, Canada geese return to their birthplaces every spring to nest and create new families. April brings about their nesting activities, as well as the first of the season’s goslings (baby geese).

Canada geese tend to always choose a nest site within 150 feet of water, with concealment from predators being ideal. The female usually has the final say on the nest, building it herself out of sticks, leaves, and some of her own feathers. When the nesting site has been built, both mates will defend it. Each day, the female goose will lay one egg until she has a clutch ranging from 2-12 eggs. Then, the female will stay at the nest, incubating them for 28 days as the male guards her. Once the eggs hatch, the adult pair will wait about 24 hours before leading them away from the nest. Both adults will defend their broods for 10-12 weeks, until they are able to fly at 70 days old.

Geese are very open to “adoption”, especially where goose populations are dense. In fact, geese may adopt several groups of goslings, forming what is coined “gang broods”. Gang broods range from 20 to 100 goslings. They only have a few adults though, usually less than four. When this involves friendly parent pairs, it can be thought of as cooperative, as this ensures there is always at least one adult goose near the goslings for protection while the others are free to forage. However, sometime this is hostile, with geese pairs being aggressive and stealing goslings away from weaker parents to pad their own brood. The thieving pair’s original goslings stay closer to them, allowing the stolen goslings to be easier prey to predators. In this way, this better ensures the survival of their original brood to adulthood.

Surviving goslings will stay with their parents for their first year, and sometimes even their second. As they mature, they will become more social, gathering to feed in large numbers when food is plentiful. Once they are around 3 years old, they begin to pair off, finding mates of their own.

So next time you start to be annoyed with all the honking and geese poop that April brings to the nature center, remember that soon enough, there will be plenty of cute goslings to make it all worthwhile!

Author: Kendalynn Ross – Teacher/Naturalist Intern

Canada geese tend to always choose a nest site within 150 feet of water, with concealment from predators being ideal. The female usually has the final say on the nest, building it herself out of sticks, leaves, and some of her own feathers. When the nesting site has been built, both mates will defend it. Each day, the female goose will lay one egg until she has a clutch ranging from 2-12 eggs. Then, the female will stay at the nest, incubating them for 28 days as the male guards her. Once the eggs hatch, the adult pair will wait about 24 hours before leading them away from the nest. Both adults will defend their broods for 10-12 weeks, until they are able to fly at 70 days old.

Geese are very open to “adoption”, especially where goose populations are dense. In fact, geese may adopt several groups of goslings, forming what is coined “gang broods”. Gang broods range from 20 to 100 goslings. They only have a few adults though, usually less than four. When this involves friendly parent pairs, it can be thought of as cooperative, as this ensures there is always at least one adult goose near the goslings for protection while the others are free to forage. However, sometime this is hostile, with geese pairs being aggressive and stealing goslings away from weaker parents to pad their own brood. The thieving pair’s original goslings stay closer to them, allowing the stolen goslings to be easier prey to predators. In this way, this better ensures the survival of their original brood to adulthood.

Surviving goslings will stay with their parents for their first year, and sometimes even their second. As they mature, they will become more social, gathering to feed in large numbers when food is plentiful. Once they are around 3 years old, they begin to pair off, finding mates of their own.

So next time you start to be annoyed with all the honking and geese poop that April brings to the nature center, remember that soon enough, there will be plenty of cute goslings to make it all worthwhile!

Author: Kendalynn Ross – Teacher/Naturalist Intern

May- The American white pelican

Photo by Ron Dudley

Photo by Ron Dudley

"I will never forget the first time I saw a pelican. It was mid-April, and I was visiting Myre Island State Park after the frost had thawed. I took a trip to one of my favorite hiking spots looking for spring beauties and bloodroot, but saw instead a flock of massive, floating white birds on the lake. What I knew then of pelicans was limited; they have funky bills, like to eat fish, and didn’t live where I grew up. So when I saw one for the first time, I couldn’t believe it; with their bright orange beaks, black wing tips, and incredible stature, they were well worth the wait.

There are 8 species of birds in the genus Pelecanus, which are known for their large, long beak and their throat pouch, or gular pouch (gular translates to “throat” in Latin). Pelicans are one of the largest living birds; some in the genus can weigh up to 30 pounds (nearly 15 times the weight of a barred owl, and twice the weight of a Canada goose!) The American white pelican can be 5 feet tall with a wingspan of up to 9.5 feet.

Pelicans are set apart not only by their size, but also by their unique eating behavior. They eat by scooping up to 3 gallons of water with into their bill, then opening their bill slightly to let the water out while keeping their food in. Their diet consists of fish, crayfish, and salamanders; if it can fit in their pouch, it can be swallowed. A common misconception about pelicans is that they keep fish in their gular pouch until they want to eat; in fact, they eat right away. They regurgitate food for their young, but otherwise swallow their food whole once the water has been sieved from their bill.

Minnesota is one of the most populous breeding sites for American white pelicans, along with North and South Dakota. Their range is largely limited to western North America, but seem to like our neck of the woods the best. American white pelicans are monogamous, and choose their mate based on their partners’ ability to strut, bow, and the males ability to grow a nice orange caruncle (shown in the photograph) on their beak.

Pelicans nest in colonies, sometimes with thousands, and create nests by digging into sand, soil, or gravel. Females often lay a clutch of 2 eggs, and both parents take turns incubating until they hatch. After they hatch, however, the second chick hatched often doesn’t survive into adulthood. Despite this, American white pelican populations are doing well, and their population status is of least concern."

Author: Office Manager/Naturalist - Meredith Maloney

There are 8 species of birds in the genus Pelecanus, which are known for their large, long beak and their throat pouch, or gular pouch (gular translates to “throat” in Latin). Pelicans are one of the largest living birds; some in the genus can weigh up to 30 pounds (nearly 15 times the weight of a barred owl, and twice the weight of a Canada goose!) The American white pelican can be 5 feet tall with a wingspan of up to 9.5 feet.

Pelicans are set apart not only by their size, but also by their unique eating behavior. They eat by scooping up to 3 gallons of water with into their bill, then opening their bill slightly to let the water out while keeping their food in. Their diet consists of fish, crayfish, and salamanders; if it can fit in their pouch, it can be swallowed. A common misconception about pelicans is that they keep fish in their gular pouch until they want to eat; in fact, they eat right away. They regurgitate food for their young, but otherwise swallow their food whole once the water has been sieved from their bill.

Minnesota is one of the most populous breeding sites for American white pelicans, along with North and South Dakota. Their range is largely limited to western North America, but seem to like our neck of the woods the best. American white pelicans are monogamous, and choose their mate based on their partners’ ability to strut, bow, and the males ability to grow a nice orange caruncle (shown in the photograph) on their beak.

Pelicans nest in colonies, sometimes with thousands, and create nests by digging into sand, soil, or gravel. Females often lay a clutch of 2 eggs, and both parents take turns incubating until they hatch. After they hatch, however, the second chick hatched often doesn’t survive into adulthood. Despite this, American white pelican populations are doing well, and their population status is of least concern."

Author: Office Manager/Naturalist - Meredith Maloney

2023 NATURE NOTES

January - Damp vs dry cold

In my family (and in the office here at the Nature Center) most of us generally agree that damp cold is worse than dry cold. Because of how unanimous this opinion was, I had naively assumed that there must be some sort of scientific understanding as to why humid air during the winter time feels so much colder than dry air. Well, I was surprised to learn that there in fact is not a clear scientific explanation for why we feel this way.

When we talk about humidity in the air, we are actually talking about a ratio called relative humidity. Relative humidity is the amount of water vapor in the air in comparison to the maximum amount of water vapor the atmosphere could theoretically hold – it’s often expressed as a percentage. This is what we are referring to when we complain about high humidity in the summertime. Our bodies are masters of thermoregulation (that’s a fancy word for controlling our inner body temperature). When we are hot, we produce sweat in order to cool down. Our sweat evaporates from our skin, turning into water vapor and entering the atmosphere. With high humidity though, little to no additional water vapor can enter the atmosphere, which means our sweat can’t evaporate and help us cool down. That’s why on hot and muggy days, we actually do feel hotter, and there’s a scientific reason behind it.

So, what happens when it’s cooler? When the temperature is around 50 degrees, we do tend to feel colder when it is humid compared to when it is dry. This is because the extra moisture in the air comes into contact with our skin and clothes. That moisture then evaporates using some of our body heat as energy, enhancing heat loss. So then why doesn't this explanation add up when it's colder out? When temperatures fall below freezing, the maximum amount of water that the atmosphere can hold is miniscule to begin with. That means there isn’t actually a significant difference in the amount of water vapor in the air on a ‘damp’ vs a ‘dry’ winter day. A winter day is just plain dry regardless of the relative humidity.

If that’s the case, you may be wondering why some people insist that it feels colder on a damp winter day than on a dry day. There isn’t much research to back up either claim, and the difficulty in studying this topic comes from the fact that ‘feeling cold’ is very subjective. There are a couple less scientific explanations nonetheless: 1) we simply associate damp days with clouds and precipitation, and the sun is warm (think about how a cloudy, snowy 20-degree day feels much colder than a sunny one) and 2) we associate damp weather with slush and warmer temperatures, and therefore dress less appropriately for the weather. Ditching our windproof winter coats and extra gear like scarves, gloves, and hats makes us less prepared for the cold, making us feel colder, when we’ve actually brought the coldness upon ourselves.

By Akiko Nakagawa Naturalist Intern

When we talk about humidity in the air, we are actually talking about a ratio called relative humidity. Relative humidity is the amount of water vapor in the air in comparison to the maximum amount of water vapor the atmosphere could theoretically hold – it’s often expressed as a percentage. This is what we are referring to when we complain about high humidity in the summertime. Our bodies are masters of thermoregulation (that’s a fancy word for controlling our inner body temperature). When we are hot, we produce sweat in order to cool down. Our sweat evaporates from our skin, turning into water vapor and entering the atmosphere. With high humidity though, little to no additional water vapor can enter the atmosphere, which means our sweat can’t evaporate and help us cool down. That’s why on hot and muggy days, we actually do feel hotter, and there’s a scientific reason behind it.

So, what happens when it’s cooler? When the temperature is around 50 degrees, we do tend to feel colder when it is humid compared to when it is dry. This is because the extra moisture in the air comes into contact with our skin and clothes. That moisture then evaporates using some of our body heat as energy, enhancing heat loss. So then why doesn't this explanation add up when it's colder out? When temperatures fall below freezing, the maximum amount of water that the atmosphere can hold is miniscule to begin with. That means there isn’t actually a significant difference in the amount of water vapor in the air on a ‘damp’ vs a ‘dry’ winter day. A winter day is just plain dry regardless of the relative humidity.

If that’s the case, you may be wondering why some people insist that it feels colder on a damp winter day than on a dry day. There isn’t much research to back up either claim, and the difficulty in studying this topic comes from the fact that ‘feeling cold’ is very subjective. There are a couple less scientific explanations nonetheless: 1) we simply associate damp days with clouds and precipitation, and the sun is warm (think about how a cloudy, snowy 20-degree day feels much colder than a sunny one) and 2) we associate damp weather with slush and warmer temperatures, and therefore dress less appropriately for the weather. Ditching our windproof winter coats and extra gear like scarves, gloves, and hats makes us less prepared for the cold, making us feel colder, when we’ve actually brought the coldness upon ourselves.

By Akiko Nakagawa Naturalist Intern

February - the wiley coyote

February is prime time to listen for your neighborhood family of coyotes. But their vocalizations are no cause for alarm.

Coyotes are often seen as pests and nuisances with their wiley and cunning tendencies. They get a bad rap for going after livestock, pets, or local fauna. But in reality this canine is highly adaptable and has flourished with the boom of the human species, so are they really all bad?

Wolves, foxes, coyotes, and dogs are all in the same biological family of Canidea. And wolves and coyotes are even closer related belonging to the same genus of canis. So why do wolves get a better PR than coyotes do? They both hunt the same prey and have similar impacts on their ecosystems.

As the human population started to expand and have a need for more land for towns, farms, and everything in between coyotes seemed to thrive while wolves were seen more as a threat. That threat triggered an overhunting while people tried to eradicate the wolves for the safety of their livestock and families. Meanwhile, as humans swept through the land in the late 1800’s with a trail of deforestation in their wake, coyotes got to expand their range and thrive.

In more recent history, however, wolves have gotten a rebranding and seen as an elusive and majestic beast that once roamed these lands that can now only be found in “wilder” places while coyotes are the local nuisance. But even if they are a pest to us humans, coyotes have really stepped up to help fill the role of predator in a lot of ecosystems that have relied on other larger predators that have been extirpated like wolves and mountain lions.

In February the coyotes will start their search for a mate to have pups. They mate for life and search for a partner via a series of calls, yips, and howls. Because these canines are so vocal and have over 10 different kinds of calls a lot of people overestimate how many coyotes they hear in the distance. What sounds like 10 or more coyotes might only be 2 or 3. They will become noisy when in search for a mate, defending their territory, or a recent meal.

Coyotes usually live in family groups but do their hunting alone for most of their prey. If the prey is something bigger, like a dear, they have no problems teaming up. They are capable of running up to 43 miles per hour making them one of the fastest animals in North America! Their agility is helpful when on the hunt as well as their keen sight and hearing.

Being the highly adaptable animals that they are coyotes are very opportunistic. If a hunt is unsuccessful coyotes can be omnivores so eat a huge variety of things, whether its fresh meat from a kill, meat from a dead animal that has been sitting for weeks (called carrion), insects, plants, fruits, and veggies.

Although the rapport of these canines trend more towards the negative, they are a huge help in local pest control. A singular coyote can eat over 1,800 rodents a year! Talk about easy pest control. Coyotes are a driving factor in keeping a lot of smaller mammal populations in check, which in turn improves biodiversity in our local ecosystems (which is always a good thing). Hopefully this small article can help you grow your appreciation for this highly underrated local.

By Kelly Bahl, Outreach Naturalist

Coyotes are often seen as pests and nuisances with their wiley and cunning tendencies. They get a bad rap for going after livestock, pets, or local fauna. But in reality this canine is highly adaptable and has flourished with the boom of the human species, so are they really all bad?

Wolves, foxes, coyotes, and dogs are all in the same biological family of Canidea. And wolves and coyotes are even closer related belonging to the same genus of canis. So why do wolves get a better PR than coyotes do? They both hunt the same prey and have similar impacts on their ecosystems.

As the human population started to expand and have a need for more land for towns, farms, and everything in between coyotes seemed to thrive while wolves were seen more as a threat. That threat triggered an overhunting while people tried to eradicate the wolves for the safety of their livestock and families. Meanwhile, as humans swept through the land in the late 1800’s with a trail of deforestation in their wake, coyotes got to expand their range and thrive.

In more recent history, however, wolves have gotten a rebranding and seen as an elusive and majestic beast that once roamed these lands that can now only be found in “wilder” places while coyotes are the local nuisance. But even if they are a pest to us humans, coyotes have really stepped up to help fill the role of predator in a lot of ecosystems that have relied on other larger predators that have been extirpated like wolves and mountain lions.

In February the coyotes will start their search for a mate to have pups. They mate for life and search for a partner via a series of calls, yips, and howls. Because these canines are so vocal and have over 10 different kinds of calls a lot of people overestimate how many coyotes they hear in the distance. What sounds like 10 or more coyotes might only be 2 or 3. They will become noisy when in search for a mate, defending their territory, or a recent meal.

Coyotes usually live in family groups but do their hunting alone for most of their prey. If the prey is something bigger, like a dear, they have no problems teaming up. They are capable of running up to 43 miles per hour making them one of the fastest animals in North America! Their agility is helpful when on the hunt as well as their keen sight and hearing.

Being the highly adaptable animals that they are coyotes are very opportunistic. If a hunt is unsuccessful coyotes can be omnivores so eat a huge variety of things, whether its fresh meat from a kill, meat from a dead animal that has been sitting for weeks (called carrion), insects, plants, fruits, and veggies.

Although the rapport of these canines trend more towards the negative, they are a huge help in local pest control. A singular coyote can eat over 1,800 rodents a year! Talk about easy pest control. Coyotes are a driving factor in keeping a lot of smaller mammal populations in check, which in turn improves biodiversity in our local ecosystems (which is always a good thing). Hopefully this small article can help you grow your appreciation for this highly underrated local.

By Kelly Bahl, Outreach Naturalist

MARCH - Maple Syruping

It’s that time of year again where maple sap is flowing directly into the veins of the staff here at the Jay C. Hormel Nature Center. March is the time of year when the nights still reach temperatures of below freezing and the days reach warmer temperatures of 40-50 degrees. These changes in temperature allow sap to flow steadily from the trees of Silver maples at the Nature Center. The Trees know when to start producing sap based on these temperature changes! Fluctuation between above and below freezing lets the tree know that it is spring and time to form new leaves. Sap is a necessary form of energy and nutrients for trees to make those new leaves. But because sap is mostly water, if it stays above ground in the trunk of the tree, the sap will freeze and expand overnight when it is below freezing and cause damage to the tree. It could expand so much that the tree would bust open! That's why sap moves up and down the tree during this time in the spring specifically. During freezing temps the sap will travel into the roots below the freeze line in the ground as to not cause damage. This up and down movement is what allows us to 'catch' the sap as it runs through the tree in early spring.

Our buckets hope to remain full this season with sap as it takes a lot of sap to make one gallon of syrup. Sap only contains 1-6% sugar while syrup has a 66% sugar content, so in order to produce one gallon of syrup, we need 30-40 gallons of sap. How do we separate out the sugar to change sap to syrup? Our sugar shack of course! We use firewood and an evaporator to prepare the sap into syrup. To find out if the sap has turned into syrup, we can measure the temperature. The temperature of the sap needs to be at its boiling point, which is 7 degrees above the boiling point of water. The long period of being heated up allows the water to evaporate and the sugar to stay. Once golden in color, and the correct temperature and density is reached the syrup is ready to be strained and head straight into bottles ready for your kitchen table!

By: Adrianna Meiergerd, Naturalist/Teacher Intern

Our buckets hope to remain full this season with sap as it takes a lot of sap to make one gallon of syrup. Sap only contains 1-6% sugar while syrup has a 66% sugar content, so in order to produce one gallon of syrup, we need 30-40 gallons of sap. How do we separate out the sugar to change sap to syrup? Our sugar shack of course! We use firewood and an evaporator to prepare the sap into syrup. To find out if the sap has turned into syrup, we can measure the temperature. The temperature of the sap needs to be at its boiling point, which is 7 degrees above the boiling point of water. The long period of being heated up allows the water to evaporate and the sugar to stay. Once golden in color, and the correct temperature and density is reached the syrup is ready to be strained and head straight into bottles ready for your kitchen table!

By: Adrianna Meiergerd, Naturalist/Teacher Intern

APril - The bugs are back, alright!

As April approaches and frosts begin to dwindle, the ecosystems of Minnesota awaken. Green creeps back to our forests, birds return and sing for companionship, and to the dismay of many, bugs reappear. I often wondered as a kid, where did the bugs go in wintertime?

Did they die, and come back to life? Did they leave, and fly back? If they stayed here, how did they not freeze to death? Well, the answer is; sort of, yes, and seemingly by magic, but actually by some really interesting biology.

For some insects, winter is a time of feasting and growth. Invertebrates that live in streams and ponds are shielded from predators thanks to a thin layer of ice, and are insulated from harsh winds and variable temperatures. Detritivores, or invertebrates that feed on decaying matter, munch on leaves that fell off of trees in Autumn.

Insects like monarch butterflies and some species of dragonflies travel thousands of miles to Mexico for the winter, and migrate back when temperatures warm in the midwest. This feat is not widely used by insects: most grin and bear it throughout our harsh winters. Or, like japanese beetles and ladybugs, they find refuge in trees, cracks and crevices, and even our homes while waiting for sunshine.

Insects that overwinter survive using one of two methods; freeze avoidance or freeze tolerance. Freeze tolerant insects are able to survive while liquid in their body freezes, while freeze avoidant insects find ways to keep from freezing.

Freeze avoidance can be achieved in a variety of ways. Some insects purge all of the food and water in their bodies so there isn’t anything that can freeze. Some produce a waxy coating on their exoskeletons that prevents water from sticking to them and in turn, prevents them from becoming encased in ice. Some simply bury themselves in the soil to avoid predation and the bitter cold. Some even produce a chemical that is impressively similar to the antifreeze that we put in our cars!

Freeze tolerance is a truly impressive feat. In most creatures, freezing causes irreversible and life threatening damage to tissue. But in some evolutionarily bewildering insects like the woolly bear caterpillar, freezing solid is a winter survival tactic. Woolly bear caterpillars freeze in the wintertime and thaw in the springtime. Following this thaw, they can reach their final form as a woolly bear moth.

However they do it, surviving the Minnesota winter is easier said than done. So as we curse the fact that spring’s arrival leads to bugs, remember what these insects had to do in order to enjoy another season.

By: Meredith Maloney, Office Manager/Naturalist

Did they die, and come back to life? Did they leave, and fly back? If they stayed here, how did they not freeze to death? Well, the answer is; sort of, yes, and seemingly by magic, but actually by some really interesting biology.

For some insects, winter is a time of feasting and growth. Invertebrates that live in streams and ponds are shielded from predators thanks to a thin layer of ice, and are insulated from harsh winds and variable temperatures. Detritivores, or invertebrates that feed on decaying matter, munch on leaves that fell off of trees in Autumn.

Insects like monarch butterflies and some species of dragonflies travel thousands of miles to Mexico for the winter, and migrate back when temperatures warm in the midwest. This feat is not widely used by insects: most grin and bear it throughout our harsh winters. Or, like japanese beetles and ladybugs, they find refuge in trees, cracks and crevices, and even our homes while waiting for sunshine.

Insects that overwinter survive using one of two methods; freeze avoidance or freeze tolerance. Freeze tolerant insects are able to survive while liquid in their body freezes, while freeze avoidant insects find ways to keep from freezing.

Freeze avoidance can be achieved in a variety of ways. Some insects purge all of the food and water in their bodies so there isn’t anything that can freeze. Some produce a waxy coating on their exoskeletons that prevents water from sticking to them and in turn, prevents them from becoming encased in ice. Some simply bury themselves in the soil to avoid predation and the bitter cold. Some even produce a chemical that is impressively similar to the antifreeze that we put in our cars!

Freeze tolerance is a truly impressive feat. In most creatures, freezing causes irreversible and life threatening damage to tissue. But in some evolutionarily bewildering insects like the woolly bear caterpillar, freezing solid is a winter survival tactic. Woolly bear caterpillars freeze in the wintertime and thaw in the springtime. Following this thaw, they can reach their final form as a woolly bear moth.

However they do it, surviving the Minnesota winter is easier said than done. So as we curse the fact that spring’s arrival leads to bugs, remember what these insects had to do in order to enjoy another season.

By: Meredith Maloney, Office Manager/Naturalist

May - Intelligent little insects

One of the most talked about pollinators in the past few years here at the Hormel Nature Center have been our honeybees. We have already learned so much about bees, such as; the male bees do not have stingers, the female bees are the ones who go out and collect the nectar and pollen, and that bees communicate with each other through dance! Recently, there was a study that came out that shed more light on this waggle dance.

The waggle dance is such a fun thing to teach people about that we even used it in our Halloween Warm-Up skit! The waggle dance is a figure eight with different tail movements. How many times the bee makes the figure eight or which direction it moves it tail, can indicate many different things. The dance shows other worker bees which direction to fly and the flowers to pick from for the best pollen and nectar. A recent study in the journal Science, shows that bees are social learners when it comes to this dance. What does that mean? When people think of animals such as insects, they think that they are just born with the natural instincts they will need to survive. That is only partially true. The research shows that bees and other insects are capable of imitating one another and are learning how to communicate more efficiently with less errors. This was a type of social behavior that was thought to only be capable in larger brained animals, like birds and monkeys. This research may change the way all insects, especially bees, are considered when talking about the importance of their protection and endangerment status.

There has also been research done on the effects of pesticide exposure on the waggle dance. It has shown that the waggle dance changes and there are more errors in their communication. But still insects struggle to get legal protection due to the fact that they are not classified as wildlife in many U.S. states. Insects represent a huge share of animal species, almost 80%. They may be small but they pack a huge punch when it comes to how much they do for our ecosystem; pollinating, enrich soil, and provide a critical protein source for many species up the food chain. But, they are hard to monitor and there is a lot of diversity among them, leading some people to say that it is too hard to put a protection status on them. Even when some states are trying to make policies to help conserve and protect insects, they usually end up low on the priority list, even though they feed most of the animals higher on the conservation priority list!

We are still learning more every day about the importance of insects, from pollinating to feeding other animals. Hopefully with this new research showing that bees are capable of social learning people will start to look at insects in a new light. Which will hopefully lead to more protection efforts in the future. In the meantime, the pond area at the Hormel Nature Center is a perfect place to look for new and interesting insects. I challenge you to find and learn about one new insect a month this spring and summer, because the more we learn about insects, the more we will want to protect them!

Author: Sydney Weisinger: Teacher/Naturalist

The waggle dance is such a fun thing to teach people about that we even used it in our Halloween Warm-Up skit! The waggle dance is a figure eight with different tail movements. How many times the bee makes the figure eight or which direction it moves it tail, can indicate many different things. The dance shows other worker bees which direction to fly and the flowers to pick from for the best pollen and nectar. A recent study in the journal Science, shows that bees are social learners when it comes to this dance. What does that mean? When people think of animals such as insects, they think that they are just born with the natural instincts they will need to survive. That is only partially true. The research shows that bees and other insects are capable of imitating one another and are learning how to communicate more efficiently with less errors. This was a type of social behavior that was thought to only be capable in larger brained animals, like birds and monkeys. This research may change the way all insects, especially bees, are considered when talking about the importance of their protection and endangerment status.

There has also been research done on the effects of pesticide exposure on the waggle dance. It has shown that the waggle dance changes and there are more errors in their communication. But still insects struggle to get legal protection due to the fact that they are not classified as wildlife in many U.S. states. Insects represent a huge share of animal species, almost 80%. They may be small but they pack a huge punch when it comes to how much they do for our ecosystem; pollinating, enrich soil, and provide a critical protein source for many species up the food chain. But, they are hard to monitor and there is a lot of diversity among them, leading some people to say that it is too hard to put a protection status on them. Even when some states are trying to make policies to help conserve and protect insects, they usually end up low on the priority list, even though they feed most of the animals higher on the conservation priority list!

We are still learning more every day about the importance of insects, from pollinating to feeding other animals. Hopefully with this new research showing that bees are capable of social learning people will start to look at insects in a new light. Which will hopefully lead to more protection efforts in the future. In the meantime, the pond area at the Hormel Nature Center is a perfect place to look for new and interesting insects. I challenge you to find and learn about one new insect a month this spring and summer, because the more we learn about insects, the more we will want to protect them!

Author: Sydney Weisinger: Teacher/Naturalist

JUNE - slow down for the turtles!

May brought hundreds of young learners to the nature center to learn all about different critters. A favorite in nearly every class were the turtles! Seen basking on the logs in our pond or cutely swimming along with only their heads poking out of the water, the nature center is home to many, many turtles. Did you know Minnesota is home to 9 species of native turtles?? Three species of map turtles, two softshell turtles, the painted and snapping turtle, and finally two threatened species, the wood turtle and the Blanding’s turtle.

You might notice more turtles out and about on the road this month and wonder why they’ve left their usual wetland habitats – it’s because nesting season has arrived! Females are on the move to look for suitable grounds for laying their precious eggs. In the process, they may have to cross roads, so it’s important to slow down for turtles this month – those ladies are on an important mission! Let’s take a deep dive into a favorite of the turtles amongst the staff here at the nature center, the Blanding’s turtle. The unique biology and life history of the Blanding’s turtle makes this wonderful species especially prone to consequences of human disturbance.

The Blanding’s turtle is a beautiful species with a significantly domed shell and a bright yellow chin and throat. They often have speckles of white or yellow on their shells too. Adults average between 6-9 inches, and they are found in calm, shallow waters where aquatic vegetation is plentiful and sandy uplands are nearby. With these very specific habitat requirements, Blanding’s turtles at all stages of life have been affected by habitat destruction and fragmentation. While you may be familiar with habitat destruction, let’s quickly talk about how habitat fragmentation can result in population declines. Habitat fragmentation occurs when parts of a habitat are destroyed, leaving smaller, disconnected areas of habitat behind. Habitat fragmentation leads to isolated populations, restricting gene flow. It also creates a larger area along the edges that are exposed to human activity. Think about it like this: if a habitat for a Blanding’s turtle is fragmented by the development of roads, a female turtle may have to cross multiple roads in order to find a suitable mate or nesting site, greatly increasing the risk of getting run over.

In addition to the destruction and fragmentation of their habitats, the life history of the Blanding’s turtle also makes them more prone to getting run over. Females can travel up to 1 mile from their resident wetland habitat to find suitable nesting sites. This is significantly longer than most other species of turtles, and increases the likelihood that she will be hit by a car while travelling. Additionally, Blanding’s turtles have a long development period and do not become sexually mature until they are 12 years of age. Therefore, if a mature female is killed while trying to cross a road, it may set back the local population for many years. These nesting sites that are far away from wetlands also threaten the survival of hatchlings – they will face similar car mortality, but are also at risk of desiccation and predation when traveling from the nesting site to nearby wetlands. However, high juvenile mortality is offset by how long adults can live to be – they may live up to 100 years old!

While Blanding’s turtles have been classified as a threatened species in Minnesota since 1984, the Minnesota DNR’s Nongame Wildlife Program has been working hard to conserve and protect this species. Their project focuses on surveying existing populations and establishing priority protection areas. If you’ve spotted a Blanding’s turtle, especially here in southern Minnesota, you can report it to the Nongame Wildlife Program and assist in their conservation efforts to save this incredible species! Happy June everyone, let’s slow down for the turtles this month!

Author: Akiko Nakagawa, Teacher/Naturalist Intern

You might notice more turtles out and about on the road this month and wonder why they’ve left their usual wetland habitats – it’s because nesting season has arrived! Females are on the move to look for suitable grounds for laying their precious eggs. In the process, they may have to cross roads, so it’s important to slow down for turtles this month – those ladies are on an important mission! Let’s take a deep dive into a favorite of the turtles amongst the staff here at the nature center, the Blanding’s turtle. The unique biology and life history of the Blanding’s turtle makes this wonderful species especially prone to consequences of human disturbance.

The Blanding’s turtle is a beautiful species with a significantly domed shell and a bright yellow chin and throat. They often have speckles of white or yellow on their shells too. Adults average between 6-9 inches, and they are found in calm, shallow waters where aquatic vegetation is plentiful and sandy uplands are nearby. With these very specific habitat requirements, Blanding’s turtles at all stages of life have been affected by habitat destruction and fragmentation. While you may be familiar with habitat destruction, let’s quickly talk about how habitat fragmentation can result in population declines. Habitat fragmentation occurs when parts of a habitat are destroyed, leaving smaller, disconnected areas of habitat behind. Habitat fragmentation leads to isolated populations, restricting gene flow. It also creates a larger area along the edges that are exposed to human activity. Think about it like this: if a habitat for a Blanding’s turtle is fragmented by the development of roads, a female turtle may have to cross multiple roads in order to find a suitable mate or nesting site, greatly increasing the risk of getting run over.

In addition to the destruction and fragmentation of their habitats, the life history of the Blanding’s turtle also makes them more prone to getting run over. Females can travel up to 1 mile from their resident wetland habitat to find suitable nesting sites. This is significantly longer than most other species of turtles, and increases the likelihood that she will be hit by a car while travelling. Additionally, Blanding’s turtles have a long development period and do not become sexually mature until they are 12 years of age. Therefore, if a mature female is killed while trying to cross a road, it may set back the local population for many years. These nesting sites that are far away from wetlands also threaten the survival of hatchlings – they will face similar car mortality, but are also at risk of desiccation and predation when traveling from the nesting site to nearby wetlands. However, high juvenile mortality is offset by how long adults can live to be – they may live up to 100 years old!

While Blanding’s turtles have been classified as a threatened species in Minnesota since 1984, the Minnesota DNR’s Nongame Wildlife Program has been working hard to conserve and protect this species. Their project focuses on surveying existing populations and establishing priority protection areas. If you’ve spotted a Blanding’s turtle, especially here in southern Minnesota, you can report it to the Nongame Wildlife Program and assist in their conservation efforts to save this incredible species! Happy June everyone, let’s slow down for the turtles this month!

Author: Akiko Nakagawa, Teacher/Naturalist Intern

july - where the wild orchids are

Most Minnesotans know our state flower, the showy lady’s-slippers, but not many know that lady’s slippers are a type of orchid. In fact, the Gopher State is home to over 40 different species of native orchids. Out of those species there are 13 species that are in full bloom in the month of July. Here at the nature center, we have had history with two different orchid species.

Historically the nature center was home to a nice population of Greater Yellow Lady’s-slipper, which is one of the most common orchids found in north America in the wild. The plant reaches about 18 inches tall while the vibrant pouch like flowers reach up to 2 inches in length with curled spindly petals mimicking laces for a shoe. This beautiful native was once an abundant showstopper of our forest back in the 80s but was coveted by locals who wanted them in their yard and our population started to dwindle as patrons came and dug them up. By the mid to late 90s our entire population of Yellow Lady’s-slipper was no more.

The Jay C. Hormel Nature Center is still home to another variety of orchid that is found far into our property but makes the prairie it’s home instead of the woods. The Tubercled Rein Orchid (Platanthera flava var. herbiola) has tiny yellowish green flowers that grow up a bract from the base of the plant. The orchid can reach a height of almost 2 feet but can be tricky to spot among the tall grasses of prairie where it calls home. Back in 1984 the Tubercled Rein Orchid was designated as a state endangered species, but with the discovery of a wider, though scarce, population the species got downgraded to a threatened species in 2013. We find blooms of this orchid during the beginning of July.

The habitat for all our native orchids is declining and these plants are very sensitive to environmental changes. Meaning native orchids are a great indicator to the health of an ecosystem. Many of the almost 50 species of orchid have a parasitic relationship with fungal mycelium which runs under the soil. The orchids will feed off the fungus to get its nutrients to the point where the plants cannot survive without it. If the habitat gets disturbed and the fungal growth gets interrupted, the orchids lose their food source. Even the seeds of our native orchids don’t have any substance to them at all and depend on some fungal friends. No casing for protection, no extra food attached, and they are super fine particle-like seeds called dust seeds. The almost microscopic seeds are housed in a seed capsule that could contain thousands of seeds without any food to start growing. Once they hit the ground they’ll try and utilize any fungal relationship they can find to grow into a new plant. The success rate in the wild is low and is not much better with the help of human intervention. Scientists have started to study and propagate wild native orchids to help with the conservation of as many species as possible, but they do not have a lot of information, experience, nor research out there about our non-tropical orchids.

As a reminder to anyone who enjoys the outdoors and especially finding unique and beautiful flowers wherever they go, to only take pictures back with you! These types of plants are sensitive to their environment and play a larger part in the entire ecosystem, as is true with all native plants. If you end up finding any orchids during your time at the nature center, consider yourself lucky. We hope you get the chance.

Author: Kelly Bahl, Outreach Naturalist/Teacher

Historically the nature center was home to a nice population of Greater Yellow Lady’s-slipper, which is one of the most common orchids found in north America in the wild. The plant reaches about 18 inches tall while the vibrant pouch like flowers reach up to 2 inches in length with curled spindly petals mimicking laces for a shoe. This beautiful native was once an abundant showstopper of our forest back in the 80s but was coveted by locals who wanted them in their yard and our population started to dwindle as patrons came and dug them up. By the mid to late 90s our entire population of Yellow Lady’s-slipper was no more.

The Jay C. Hormel Nature Center is still home to another variety of orchid that is found far into our property but makes the prairie it’s home instead of the woods. The Tubercled Rein Orchid (Platanthera flava var. herbiola) has tiny yellowish green flowers that grow up a bract from the base of the plant. The orchid can reach a height of almost 2 feet but can be tricky to spot among the tall grasses of prairie where it calls home. Back in 1984 the Tubercled Rein Orchid was designated as a state endangered species, but with the discovery of a wider, though scarce, population the species got downgraded to a threatened species in 2013. We find blooms of this orchid during the beginning of July.

The habitat for all our native orchids is declining and these plants are very sensitive to environmental changes. Meaning native orchids are a great indicator to the health of an ecosystem. Many of the almost 50 species of orchid have a parasitic relationship with fungal mycelium which runs under the soil. The orchids will feed off the fungus to get its nutrients to the point where the plants cannot survive without it. If the habitat gets disturbed and the fungal growth gets interrupted, the orchids lose their food source. Even the seeds of our native orchids don’t have any substance to them at all and depend on some fungal friends. No casing for protection, no extra food attached, and they are super fine particle-like seeds called dust seeds. The almost microscopic seeds are housed in a seed capsule that could contain thousands of seeds without any food to start growing. Once they hit the ground they’ll try and utilize any fungal relationship they can find to grow into a new plant. The success rate in the wild is low and is not much better with the help of human intervention. Scientists have started to study and propagate wild native orchids to help with the conservation of as many species as possible, but they do not have a lot of information, experience, nor research out there about our non-tropical orchids.

As a reminder to anyone who enjoys the outdoors and especially finding unique and beautiful flowers wherever they go, to only take pictures back with you! These types of plants are sensitive to their environment and play a larger part in the entire ecosystem, as is true with all native plants. If you end up finding any orchids during your time at the nature center, consider yourself lucky. We hope you get the chance.

Author: Kelly Bahl, Outreach Naturalist/Teacher

August- Great Egrets Then & Now

Have you ever seen a tall snowy-white bird on the water in summer and wondered what it was? Those are great egrets. They are in the heron family. While most people use the terms “heron” and “egret” loosely, most egrets are white. This sleek white bird can reach heights of over 3 feet tall, with a long yellow beak and black stilt-like legs. During mating season, the patch on their face turns a lime green and their back feathers grow into an elegant plume. Although the fanciful feathers of this bird do a great job attracting a mate, it has a long, more complex history that extends out of the realm of birds.

In the late 1800s it became fashionable to wear plumes from wild birds in ladies’ hats. The birds most affected by this hunting were egrets, ostriches, birds of paradise, pheasants, peacocks, and quails. They were often shot in the spring when their feathers were the most colorful for mating season. In turn, this decreased the number of nesting birds, which drastically decreased the population in a short period of time. In the end almost 5 million birds were killed for their plumes and feathers.

Concerned citizens started speaking out against the hunting of these birds en masse. In fact, the outrage about the slaughter of millions of birds just for the sake of fashion is what first sparked the establishment of the Audubon Society in 1896. With the help of the newly formed Audubon Society and President Roosevelt, Pelican Island was established as the first national wildlife sanctuary to protect egrets and other birds from plume hunters. Other popular plume hunting areas followed suit and started to protect popular nesting grounds for these birds. Slowly the population began to increase as more awareness was spread about these birds and the devastating effects of plume hunting. As a result of the success of the National Audubon Society’s first campaign, the great egret became their symbol which remains today.

In present times, the range of the great egret continues to expand. Here in southern Minnesota, we can see a dozen or more egrets standing together on the edge of lakes, marshes, and swamps during August and early September in line with their fall migration. Collectively, great egrets have been moving further north in Minnesota since the 1930s. They became regular migrants and summer residents in southern Minnesota in the 1950s. The farthest north nests of great egrets have been found is in Marshall County in 1980. Since we are coming to the end of summer, great egrets will start migrating south towards the southern states in the U.S., Mexico, and Central America.

Even though back in the 19th century the great egret was almost hunted to extinction, there is an estimated 1-2 million of these birds out in the wild today. They are classified with a least concern conservation status and are considered as an excellent example of a successful conservation campaign. If you miss them in the fall migration, they will be back around mid-April. Be on the lookout for 3ft wide platform nests that are 20-40 feet off the ground near a water source. We have some great habitat in town along the Cedar River that is perfect for herons and egrets alike, so keep your eyes peeled along the edge of the water or way up in the riverside trees for this fun birding find!

Author: Sydney Weisinger – Teacher/Naturalist

In the late 1800s it became fashionable to wear plumes from wild birds in ladies’ hats. The birds most affected by this hunting were egrets, ostriches, birds of paradise, pheasants, peacocks, and quails. They were often shot in the spring when their feathers were the most colorful for mating season. In turn, this decreased the number of nesting birds, which drastically decreased the population in a short period of time. In the end almost 5 million birds were killed for their plumes and feathers.

Concerned citizens started speaking out against the hunting of these birds en masse. In fact, the outrage about the slaughter of millions of birds just for the sake of fashion is what first sparked the establishment of the Audubon Society in 1896. With the help of the newly formed Audubon Society and President Roosevelt, Pelican Island was established as the first national wildlife sanctuary to protect egrets and other birds from plume hunters. Other popular plume hunting areas followed suit and started to protect popular nesting grounds for these birds. Slowly the population began to increase as more awareness was spread about these birds and the devastating effects of plume hunting. As a result of the success of the National Audubon Society’s first campaign, the great egret became their symbol which remains today.

In present times, the range of the great egret continues to expand. Here in southern Minnesota, we can see a dozen or more egrets standing together on the edge of lakes, marshes, and swamps during August and early September in line with their fall migration. Collectively, great egrets have been moving further north in Minnesota since the 1930s. They became regular migrants and summer residents in southern Minnesota in the 1950s. The farthest north nests of great egrets have been found is in Marshall County in 1980. Since we are coming to the end of summer, great egrets will start migrating south towards the southern states in the U.S., Mexico, and Central America.

Even though back in the 19th century the great egret was almost hunted to extinction, there is an estimated 1-2 million of these birds out in the wild today. They are classified with a least concern conservation status and are considered as an excellent example of a successful conservation campaign. If you miss them in the fall migration, they will be back around mid-April. Be on the lookout for 3ft wide platform nests that are 20-40 feet off the ground near a water source. We have some great habitat in town along the Cedar River that is perfect for herons and egrets alike, so keep your eyes peeled along the edge of the water or way up in the riverside trees for this fun birding find!

Author: Sydney Weisinger – Teacher/Naturalist

September - Fall colors in September?

The warm sunny days of summer are coming to a close as we are on to school days and pumpkin spice lattes. Here in Southern Minnesota, we notice our trees turning color a bit earlier this year. Due to warm weather paired with many weeks of drought, our trees are beginning to turn color earlier than they have in the past.

Drought affects many of our plants in our ecosystem, but most apparent this season are the trees. During drought events, trees can often go into early dormancy. The fall season is when many trees go into dormancy to conserve and store energy to grow and reproduce in the following spring. This year, dormancy for trees is starting earlier because the trees have gone through immense stress due to unseasonably hot weather and drought. They will preserve their energy and save resources to survive another year by shutting down their growth processes early. While trees normally grow full green leaves through the summer season, you may notice that trees are beginning to drop leaves right now. Early leaf dropping is one way a tree can conserve water it needs for growth. Leaves typically release water vapor during normal growth processes, however during drought, the leaves close their pores to prevent that water loss. Trees need to conserve water in their own systems to produce buds in the spring and roots throughout the year. As for this year, trees are dropping these leaves to conserve additional energy making fall start a little bit earlier.

The changing of seasons is always an exciting time. Leaves are beginning to fall which means passing the time by raking leaves and watching for squirrels prepare for winter. So as fall vibes start a little early this year be sure to check out some of our favorite native trees.

The Ohio Buckeye tree is a favorite of Southern Minnesota residents since its fall leaves are striking bright hues of red. These trees are starting to produce fruit which ripens mid September! Their fruit is rather spikey looking and contains one to three seeds. These seeds are easily identifiable, especially if you’re an Ohio State fan. There are many people who covet the seeds of the Buckeye tree as they are said to bring good luck! These trees range from Texas, to Nebraska, and even as far as Pennsylvania. You will see them start to change color from green to bright yellows and reds during the fall season.

Another tree you’ll find in bright colors is the Sumac. Usually considered to be a small tree or Shrub, sumac ranges in height from 3 feet tall to over 30. Minnesota is home to two types of sumac trees, the smooth and staghorn Sumac. Southern Minnesota has a wide span for the staghorn Sumac whereas northern Minnesota finds very few of the staghorn variety. Both varieties produce a fuzzy red fruit which many wild animals enjoy eating. Even their leaves change into a bright red color during the fall months. See if you can spot both varieties of Sumac trees this year.

Author: Adrianna Meiergerd, Teacher/Naturalist Intern

Drought affects many of our plants in our ecosystem, but most apparent this season are the trees. During drought events, trees can often go into early dormancy. The fall season is when many trees go into dormancy to conserve and store energy to grow and reproduce in the following spring. This year, dormancy for trees is starting earlier because the trees have gone through immense stress due to unseasonably hot weather and drought. They will preserve their energy and save resources to survive another year by shutting down their growth processes early. While trees normally grow full green leaves through the summer season, you may notice that trees are beginning to drop leaves right now. Early leaf dropping is one way a tree can conserve water it needs for growth. Leaves typically release water vapor during normal growth processes, however during drought, the leaves close their pores to prevent that water loss. Trees need to conserve water in their own systems to produce buds in the spring and roots throughout the year. As for this year, trees are dropping these leaves to conserve additional energy making fall start a little bit earlier.